Emergency Prehospital Care for COPD Patients

Written by: Sherehan Wahid

Edited By: Adam Jones

Introduction to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a long-term, progressive, respiratory condition characterised by persistent airflow limitation and difficulty breathing, primarily due to inflammation and structural changes in the lungs. It is an umbrella term that includes two main conditions:

Chronic Bronchitis – Inflammation of the bronchi (the lung’s airways), leading to excessive mucus production and a chronic productive cough.

Emphysema – Destruction of the alveoli (air sacs in the lungs) and loss of their elasticity, resulting in impaired gas exchange and breathlessness.

COPD can often present as an acute emergency during exacerbations, most commonly triggered by respiratory infections or environmental irritants.

Pathophysiology Of COPD

COPD is marked by persistent airflow limitation due to an abnormal inflammatory response in the lungs to harmful particles and gases, notably cigarette smoke. While all smokers exhibit some degree of lung inflammation, individuals who develop COPD experience an intensified or atypical response.

This heightened inflammation can lead to:

Mucous hypersecretion – this results in chronic bronchitis

Tissue destruction – at a cellular level the lung parenchyma would demonstrate the destruction of alveolar walls, reducing the surface area for gas exchange and this results in emphysema

Disruption of repair mechanisms – causing small airway inflammation and fibrosis, known as bronchiolitis.

These pathological changes increase resistance in the small airways, cause air trapping and carbon dioxide retention, culminating in progressive airflow obstruction.

COPD Prevalence and Incidence

In the UK alone, COPD is reported to have affected around 3 million people with only one third of them being officially diagnosed. This is due to the dismissal of COPD symptoms as other conditions like ‘smoker’s cough’, which leads many people to not seek medical help. COPD also accounts for around 1.4 million GP consultations a year and is the second most common cause of emergency admissions to hospitals.

Risk Factors Of COPD

Several factors may increase the risk of developing COPD:

Tobacco Smoking

Tobacco smoking is the leading risk factor for COPD, accounting for approximately 90% of cases. While cigarette smoking is most strongly linked, the use of pipes, cigars, and marijuana, as well as exposure to passive smoking, can also significantly increase the risk.

Occupational Exposure

Occupational exposure plays a key role, with around one fifth of COPD cases attributed to prolonged contact with dust, fumes, vapours, and chemical irritants in the workplace.

Genetic Factors

Genetic factors, though less common, can contribute to COPD. The most notable example is alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, a hereditary condition that impairs lung protection mechanisms, making individuals more susceptible to lung damage.

Other

Other important risk factors include exposure to indoor air pollutants (such as biomass fuel used for cooking or heating), maternal smoking during pregnancy, and a history of asthma, which can increase long-term susceptibility to chronic airflow limitation.

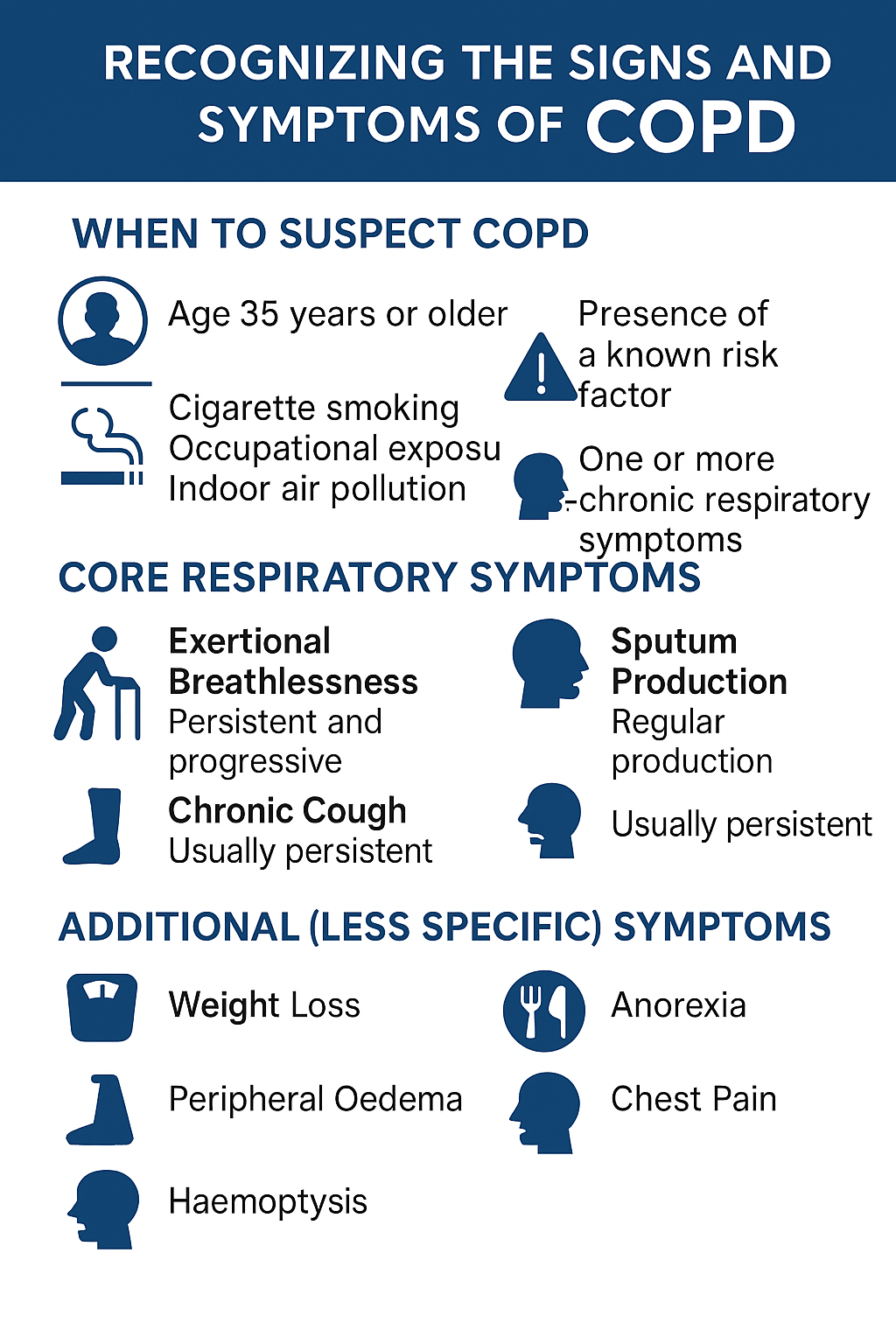

Signs & Symptoms of COPD

Early identification is essential for improving outcomes, slowing disease progression, and optimising quality of life.

COPD should be considered in individuals who meet all three of the following criteria:

1 – Age 35 years or older

2 – Presence of a known risk factor, such as:

Long-term cigarette smoking (current or past)

Occupational exposure to dust, fumes, or chemicals

Indoor air pollution (e.g., biomass fuel exposure)

History of frequent respiratory infections in childhood

3 – One or more chronic respiratory symptoms

These symptoms are usually gradual in onset and become more persistent over time:

Exertional Breathlessness

One of the earliest and most common symptoms

Typically progressive, starting with difficulty during vigorous activity and worsening over time

May be mistakenly attributed to aging or deconditioning

Chronic Cough

Often the first symptom to appear

Usually persistent and may be dry or productive

May be dismissed or normalised, particularly among smokers

Sputum Production

Regular production of sputum, particularly in the morning

May vary in volume and consistency

Chronic bronchitis is defined by a productive cough lasting at least three months in two consecutive years

Frequent Respiratory Infections

Recurrent episodes of “chest infections” or “winter bronchitis”

Often treated with antibiotics multiple times per year

Infections may temporarily worsen symptoms and contribute to long-term lung damage

Wheeze

May be heard during auscultation or reported by the patient

Can be mistaken for asthma but tends to be persistent and associated with other COPD features.

These symptoms may occur in more advanced COPD or in the presence of complications:

Weight Loss

Unintentional weight loss is a poor prognostic sign

Linked to increased metabolic demand and reduced appetite

Anorexia

Loss of appetite due to breathlessness, systemic inflammation, or co-existing depression

Peripheral Oedema

Swelling of the ankles or legs

May suggest cor pulmonale (right-sided heart failure secondary to lung disease)

Chest Pain

Typically non-specific and may be musculoskeletal

Persistent or pleuritic pain should prompt further investigation

Haemoptysis

Coughing up blood is uncommon in COPD

Always requires further evaluation to rule out other causes such as lung cancer or tuberculosis

Signs & Symptoms OF COPD Exacerbation

An acute exacerbation of COPD is defined as a sudden worsening of respiratory symptoms that goes beyond the patient’s usual day-to-day variation, often requiring a change in treatment.

Increased breathlessness, especially noticeable during physical activity

Increased sputum volume and change in sputum colour (purulence)

Use of accessory muscles during breathing (e.g. neck or shoulder muscles)

Chest tightness or a feeling of chest constriction

Acute confusion – may signal hypoxia, especially in older adults

Tachypnoea (rapid breathing) and/or tachycardia (increased heart rate)

Pursed-lip breathing – a compensatory technique to ease airflow

New onset cyanosis – bluish discolouration of lips or fingers due to low oxygen

New or worsening peripheral oedema – may indicate right-sided heart strain or failure

History & Assessment Of COPD Exacerbation

Early recognition of a COPD exacerbation is critical to initiate timely intervention and ensure prompt transport to the nearest appropriate hospital. Use a structured ABCDE approach, supplemented by a focused history.

The patient’s past medical history is vital in managing the exacerbation. Apart from general history, ask the patient specifically regarding:

Baseline SpO₂, and if they have had any previous problems with oxygen treatment

Previous episodes: Any past hospitalisations for COPD exacerbations?

Home oxygen use or NIV: Clarify current treatments.

Individualised Treatment Plan/Oxygen Alert Card – these outline the emergency treatment of the exacerbation, catering it to the specific requirements of the patient from their GP

Use a structured ABCDE approach to help assess COPD exacerbation.

A – Airway

Listen for wheezing, bubbling, or gurgling sounds.

Ensure airway patency; consider suctioning if secretions are compromising ventilation.

B – Breathing

Oxygen saturation: Use pulse oximetry. COPD patients may have a low baseline.

Respiratory rate: Tachypnoea is common. Assess if it’s significantly elevated (>20% above baseline).

Look for accessory muscle use, pursed-lip breathing, or chest hyperinflation.

Auscultation: May reveal wheezing, crackles, or reduced air entry.

Recognising “silent chest” or impending respiratory failure is important.

C – Circulation

Pulse: Tachycardia may indicate distress or hypoxia.

Blood pressure: Monitor closely; hypotension may require cautious fluid resuscitation.

Look for cyanosis, raised JVP, or peripheral oedema, potential signs of cor pulmonale.

D – Disability

Assess for altered mental status (e.g., confusion, drowsiness) which may signal hypercapnia.

E – Exposure

Examine for cachexia, signs of chronic disease, or infection triggers (e.g., fever, increased sputum).

A 12-lead ECG can be done if required.

COPD Investigations

Most COPD investigations are conducted in a clinical setting rather than in the prehospital environment.

Spirometry: Essential for the formal diagnosis of COPD, demonstrating persistent airflow obstruction (FEV₁/FVC < 0.7). However, it is not typically used during acute exacerbations in the prehospital or emergency setting.

Chest X-ray: Useful to exclude alternative or coexisting pathologies such as lung cancer, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, pneumothorax, or signs of heart failure.

Full Blood Count (FBC): May help identify contributing factors such as anaemia (worsening hypoxia) or polycythaemia (a compensatory response to chronic hypoxaemia).

Sputum Culture: Useful during exacerbations to identify bacterial pathogens, particularly when a secondary infection is suspected. Results can guide targeted antibiotic therapy.

Serial Home Peak Flow Measurements: May assist in differentiating COPD from asthma in uncertain cases.

ECG, Serum Natriuretic Peptides, and Echocardiography: Recommended when cardiac disease (e.g. heart failure) or pulmonary hypertension is suspected based on clinical findings such as peripheral oedema, raised JVP, or disproportionate dyspnoea.

CT Thorax: Indicated when symptoms appear disproportionate to spirometry results or if another diagnosis such as pulmonary fibrosis, bronchiectasis, or malignancy is suspected.

Serum Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Levels: Should be considered in patients with early-onset COPD, minimal smoking history, or a positive family history of lung disease. If a deficiency is confirmed, specialist referral is warranted for management along with familial screening.

Prehospital Management Of COPD Exacerbations

Patients with COPD often present to ambulance services during acute exacerbations, but COPD may also be a secondary condition in unrelated emergencies. Regardless of the primary complaint, COPD can significantly affect clinical management, particularly in relation to oxygen therapy.

Assess and position the patient for maximal comfort (usually sitting upright)

Maintain a patent airway – suction if needed

Monitor vital signs including respiratory rate, SpO₂, heart rate, and level of consciousness

Administer nebulised bronchodilators (salbutamol ± ipratropium)

Use oxygen-driven nebuliser if required, but:

Limit to short durations (6 minutes)

Monitor for signs of oxygen sensitivity

Administer prednisolone or hydrocortisone

Choose route depending on patient condition and ability to take oral medication

Apply controlled oxygen therapy

Target SpO₂: 88–92%, unless otherwise indicated (e.g., Oxygen Alert Card)

Use a Venturi mask or nasal cannulae

Be alert for Type 2 respiratory failure (hypercapnia)

If patient becomes drowsy or shows signs of reduced respiratory drive, lower oxygen concentration and provide ventilatory support as needed

Always titrate oxygen carefully to avoid worsening acidosis. Careful oxygen titration in suspected or known COPD patients is critical to prevent avoidable harm before hospital arrival.

ECG if indicated (e.g. chest pain, arrhythmias, altered consciousness)

Ventilation: If the patient does not respond to bronchodilators and steroids: Consider non-invasive ventilation (NIV).

IV fluids can be given if the patient is hypotensive

Activate appropriate support or transfer pathways

Transfer rapidly to the nearest appropriate hospital

Provide a pre-alert or clinical handover

Continue treatment during transport

Where suitable, consider alternative care pathways (e.g. referral schemes, community COPD team)

Differential Diagnosis

Given the wide range of conditions that can mimic COPD, it is essential to maintain a broad differential, particularly in atypical presentations. A thorough clinical assessment, supported by targeted investigations, is key to excluding other potentially serious or more likely pathologies as mentioned below:

Key Points

- Early recognition and oxygen titration save lives.

- Identify patients at risk of CO₂ retention, especially those with known previous episodes or an Oxygen Alert Card.

- Know the patient’s baseline SpO₂, if available (typically 88–92%).

- Use pulse oximetry to guide oxygen delivery and titrate accordingly.

- COPD patients often know their disease, listen to them.

Bibliography

Guy’s and St Thomas’ Specialist Care. (n.d.). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). https://guysandstthomasspecialistcare.co.uk/conditions/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd/

JRCALC Plus. (n.d.). Guidelines: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. https://jrcalcplusweb.co.uk/guidelines/G0390

MacNee, W. (2006). Pathology, pathogenesis, and pathophysiology. BMJ, 332(7551), 1202. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.332.7551.1202

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2024, November 8). COPD – What is COPD? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/copd

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2025, February). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease/

NHS. (2023, April 11). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-copd/